Human-centered technology embraced at ASU Digital Health Summit

Craig Norquist, a physician and the chief medical information officer for HonorHealth, gave the final keynote of the inaugural ASU Digital Health Summit on Friday, held at the ASU Thunderbird School of Global Management at the Downtown Phoenix campus. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

Digital health technology is advancing at lightning speed, but the innovation requires a human touch to ensure that everyone benefits from the advances, according to speakers at the inaugural ASU Digital Health Summit on Friday.

Digital health refers to technology such as wearable devices, telehealth, artificial intelligence and the management of all the personal data that is produced.

“If we rely only on the technology, we’re going to go nowhere,” said Michael Yudell, interim dean and professor in the College of Health Solutions at Arizona State University.

“We need the social-behavioral scientists to understand the impact of these technologies, how they intersect with different types of communities and how they will help or perhaps harm the most vulnerable among us.”

The daylong event, held at the Downtown Phoenix campus, covered a range of topics, including examples of how digital health innovations are helping people with dementia, why creating a “digital twin” can improve health care and how to make these technologies human centered so everyone benefits. The summit was sponsored by the College of Health Solutions, the new ASU Roybal Center for Older Adults Living Alone with Cognitive Decline and Google Government.

Here are some highlights:

Older adults want technology

Lifestyle interventions, such as diet and physical activity, are enormously effective in preventing chronic disease and extending life, according to Matthew Buman, professor in the College of Health Solutions and director of Precision Health Research Initiatives in the college. But those interventions require a lot of resources, such as multiple visits to multiple providers, and are difficult to implement at scale.

Digital health technologies can help.

“In fact, older adults are demanding technology to support their health,” he said.

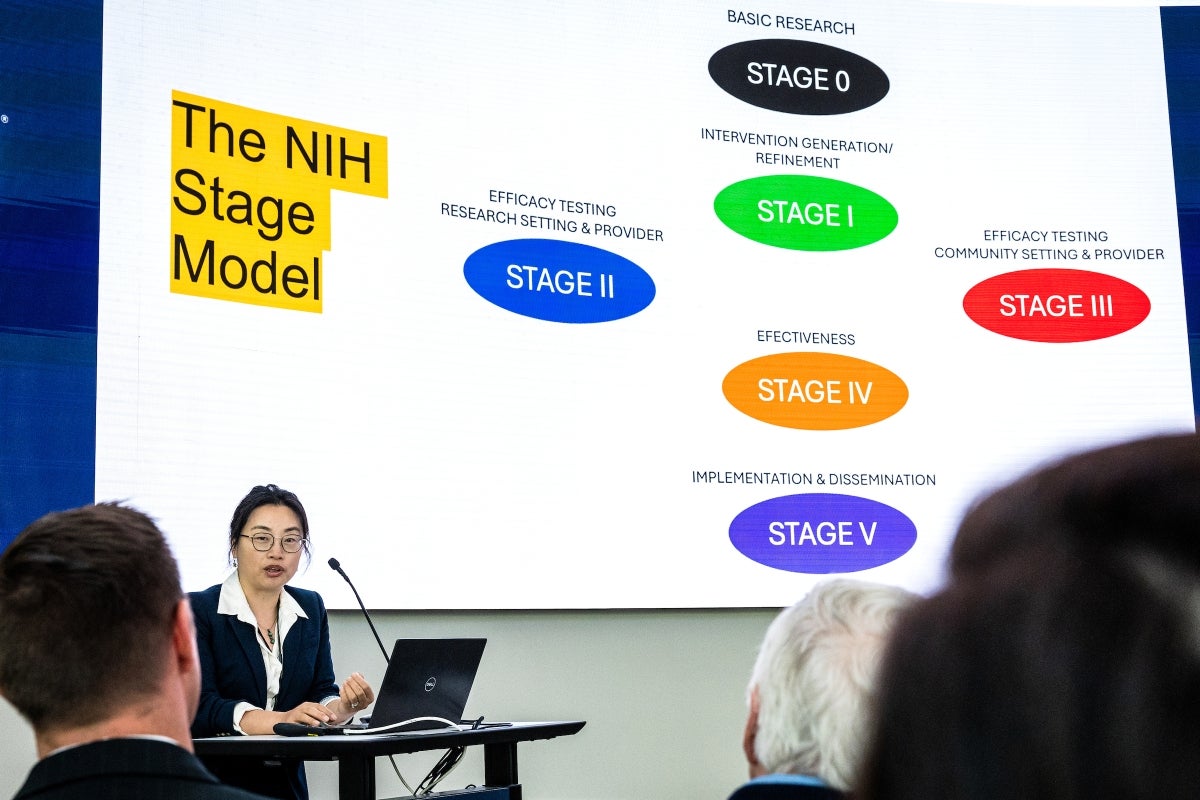

Buman participated in a keynote address with Fang Yu, professor and Edson Chair in Dementia Translational Nursing Science in the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation.

They described several studies in which digital devices help older adults and their health care teams. In one study, the goal was to reduce the amount of time older adults spent sitting and looking at screens, and how a combination of smartphone interventions, such as getting text alerts, having them earn rewards and locking them out of their screens for a set period, reduced screen time by an hour a day.

'Digital twins' for interventions

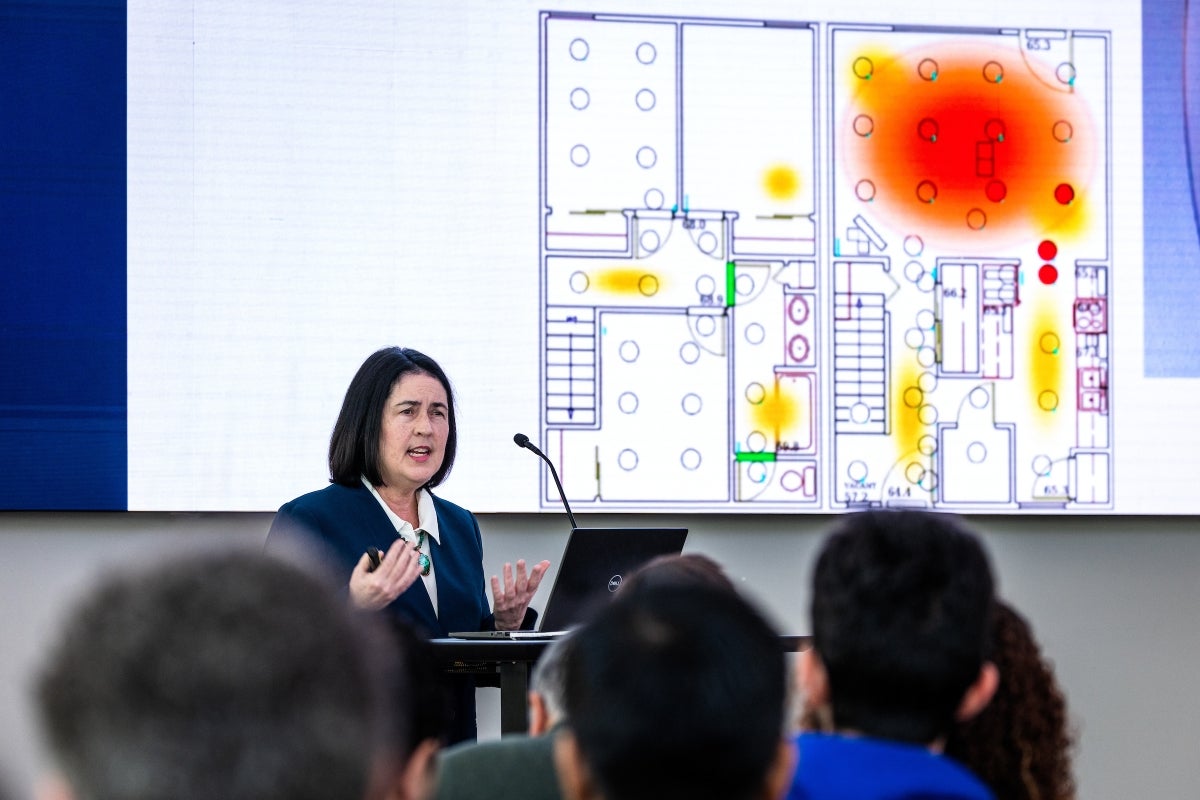

A “digital twin” is a virtual representation of a person based on data that help predict how they will respond to an intervention, according to keynote speaker Diane Cook, a professor in the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Washington State University.

For example, a patient might have type 2 diabetes but also cognitive decline.

“Let’s look at her behavior, not only to detect the correlation between behavior and changes in her physical and cognitive health, but so we can see if there are controllable behaviors that could improve her health,” she said.

The digital twin will include data on genetics, social interactions and environment.

Cook described the challenges in this method. Her lab collected data from Apple watches plus ambient sensors such as motion detectors, microphones and cameras in people’s homes. All of that can measure whether the person is leaving the house and how active they are inside, but it can’t measure functions such as how well they manage finances. Also, the subject might remove the watch, do several activities at once or live with several other people plus pets.

But there’s also promise. For example, if a patient must take medication at dinner time, the model can see that the person is about to have dinner but hasn’t taken medication and the patient can be prompted.

Creating human-centered technology

The summit included several breakout sessions in addition to the keynotes. One panel addressed “Bridging the Digital Divide: Ethics and Health Equity.”

Maissa Khatib, a research scholar in the College of Health Solutions, described how the Design and Innovation Studio for Health created the Arizona Community Cohort Model, a framework for building trust with a community.

“The whole premise is to have community engagement in the beginning of a study, identify the problems and lead the community members to have ownership of the project,” she said.

She said that access to technology such as laptops and high-speed internet connection cannot be taken for granted for some populations.

Krystal Tsosie, assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences, talked about the Native BioData Consortium in South Dakota, the first nonprofit research institute led by Indigenous geneticists and tribal members in the U.S.

Tribal communities are distrustful of granting ownership of their data to other entities, Tsosie said. “The potential stigmatization of that genetic data is very real for them."

She described how “group consent” is critical when working with tribal communities, as opposed to the Western concept of individual consent.

“That hasn’t translated well in how we structure our data models,” she explained.

“It’s going to be corporations who benefit from open-access models. They can benefit and hide behind a corporate veil of privacy.”

Beza Merid, an assistant professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society, is director of the school's Digital Health and Racial Justice Lab. He said that technology should not be viewed as a silver bullet.

“It’s important to recognize that these technologies don’t exist in a vacuum. They’re designed by people who may have biases, who may have designed based on frameworks that may be limited,” he said.

Merid said that blood pressure monitoring has advanced from the classic arm cuffs to wrist monitors and other more comfortable technology. But now work is being done to design camera sensors that can measure blood flow to the face.

“As used in racialized communities, facial recognition is inaccurate and gets misused and abused,” he said.

Fusing innovation and health care

The medical field should be quicker to embrace advances in digital health, according to Craig Norquist, an emergency physician and chief information officer with HonorHealth, the primary clinical affiliate for ASU’s new School of Medicine and Advanced Medical Engineering.

Norquist, an ultramarathoner, described how watches for athletes have evolved to measure oxygen levels and even sleep patterns but that technology was slow to be embraced in medicine.

“We have a hesitancy to try to implement new things. And there are reasons — we don't want to take a chance on our patient,” he said.

“But I think we could probably do a little bit more than we are.”

He described how the continuous glucose monitor was revolutionary for people with diabetes, who no longer had to stick their fingers before every meal.

“And when you incorporate this with the insulin pump, you basically got yourself a synthetic pancreas,” he said.

But the FDA refused to consider any technology that connected the two devices, considering it too risky. The groundbreaking innovation happened only because the patients themselves hacked the devices to make them communicate and then widely shared the information, Norquist said.

The pandemic jump-started a lot of digital innovation, such as telemedicine, he said.

A team at the University of California, San Diego, used artificial intelligence to read chest X-rays to determine if patients had COVID before there was a test for it.

“So that was forcing us to apply these tools for something other than something that's going be put in a journal,” he said.

The partnership between HonorHealth and ASU is one way to infuse innovation into health care, he said.

“Continue to iterate, make it better, make it intuitive and make it work,” he said.

More Health and medicine

Ancient DNA could help to understand recent tuberculosis outbreak in Kansas

For over a year, Wyandotte and Johnson counties in Kansas City, Kansas, have been fighting an outbreak of tuberculosis (TB) that has claimed two lives and infected nearly 150 residents. The…

ASU researchers propose unifying model of Alzheimer’s disease

In a groundbreaking theory, scientists at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute propose a unifying explanation for the molecular chaos driving Alzheimer's disease. The condition causes…

Study highlights effectiveness of 2023–24 flu vaccine and its implications for future disease preparedness

A study conducted by the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) Network, including researchers from Arizona State University, provides fresh insights into the 2023–24 flu vaccine’s performance…